Posts Tagged ‘endgame compositions’

ABOUT CHESS (And some interesting positions)

(WARNING: If after reading this post you feel absolutely confused, it’s normal. In fact the idea is to make you feel so so as to make you start thinking about Chess from, perhaps, a different point of view.)

I have mentioned this before: Does Chess build your character or simply it shows your character? The same question can be applied to music, or any other form of art. Since I was taught the game when I was a young boy and began to play seriously from 1979 onwards and official CC since 1986 , I have tried to find some explanations with a bit of non-professional self-psychoanalysis…

It is very beautiful to add a bit narrative to the matter and speak lyrically of the matter. No, that is not the way. My conclusions contain more questions than answers, more doubts than certainties and, sometimes, the answer poses more problems than the question itself…

I think Chess helps both to build the player’s character but also shows certain peculiarities of it. (Then you can notice it, maintain or try to change those findings…).In my case, for instance, Chess was a powerful tool which helped me to lose a pathological fear to taking decisions (for fear of making mistakes, accept the responsibility of them, etc.). It also helped me to avoid that common mistake in many people which consists of always looking for someone to blame for everything which happens instead of dealing with the mistakes or wrongs, and putting the effort not on finding a real or imaginary culprit but on dealing with the error straightaway.

Another point worth mentioning is to accept that everything in Chess and life is relative. There are no absolute truths, universal patterns of behaviour, hidden or occult systems to get everything at will. Chess taught me that there are many logical things and they can be good guidelines but also that there are many illogical, contradictory, absurd even apparently impossible things, situations which, nevertheless, can also take place. And the latter can be wonderful grounds to learn something new outside our old patterns . And so in the same way we must accept that there are as many ideas or opinions as people in the world, a Tal or a Shirov coexist with a Petrosian and a Karpov. In Chess, as in life, the sum of the parts is always greater to the whole itself… Contradictory? Yes. Wonderful? Again, yeah.

I think it was B. Lee, influenced by studies of different schools of philosophy, who said that “all form of knowledge is really self-knowledge”. And another reference for those interested in the matter of “self-awareness and knowing that one knows” is the medieval Islamic philosopher Avicenna (980-1037) (I have found a very interesting paper by Deborah L. Black , Department of Philosophy and Centre for Medieval Studies , University of Toronto.)

Another thing I have realized with the passing of time is that that old way of classifying chessplayers into “positional” or “attacking” ones may be helpful to a certain extent, but it can become too restrictive when not directly wrong. Take Fischer for instance: is he an attacking player? Yes, but not like Tal, so… Is he a positional player? Yes, but not like Petrosian or Karpov, so… Nevertheless, Karpov and Fischer shared their admiration for the same player: Capablanca. And this explains why those super GMs always reject being ascribed to a certain style. Karpov reacted with dislike when somebody asked him about what his Chess style was like: “Chess style?.- I don’t have a Chess style”.

I suppose “your style” is more the openings you like and the type of positions they can lead to: Fischer played 1.e4 in nearly all his games. Karpov played 1.e4 as his only first move for many years. BUT Fischer preferred reaching open positions even with no Pawn in the centre while Karpov always aimed mainly to half-open positions. (And Spassky preferred 1.e4 leading to complicated if not chaotic middlegame plans “though there is a method in it”, according to his character). You can play Sicilians Fischer/Shirov style or play Sicilians Karpov style: in one case you will be playing aggressive Najdorf variations and in the other, quiet Paulsen-Kan ones. And so on…

I have always been interested in the ideas of self-awareness, the state of alert (taken from Gudjieff), how to avoid living/acting out of sheer inertia, and how to learn not only data and facts but learning how to learn. We contemplate everything -Chess too- from behind our eyes, the world seems to always be opposite us… Can we contemplate ourselves from the other side of Chess, or rather from “inside “ Chess?. Is it possible?. Where do learning and self-learning really lie? .- Over to you…

Now the exercises will be a bit different: endgame compositions with no long solutions but really beautiful because they may represent the logical and the irrational at the same time. (Solutions below the positions)

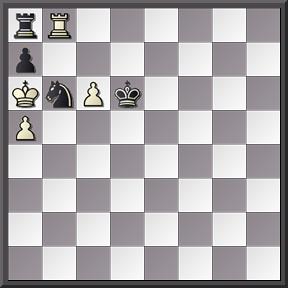

1.- Kliatskin 1924. White to move , wins. Find out how (three moves solve the problem)

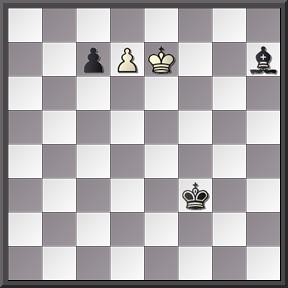

2.- Saritchev brothers 1928. White moves and manages to draw. A Kasparov’s favourite -I have read somewhere-.

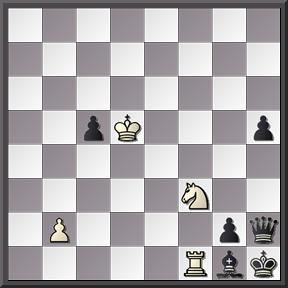

3.- Gurgenidze & Mitrofanov, 1928. White to move and wins. Difficult but beautiful.

Well, put the position on your chessboard and try to find the first move. Look it up and play the first correct one by White and Black’s reply. Keep on doing so with the rest of moves . Good luck!

Solutions:

1.- 1. c7 Rc7 (1…Nc8/2. Rb7!!) 2.ab6 Rb8 3. b7 .-

2.- 1. Rc8! b5 2. Rd7! b4 3. Rd6! Bf5 4. Ke5! Bc8 5. Kd4 Ba6 6. c8Q Bxc8 7. Kc4 It is a draw.

3.- 1. Rb1 c4 2. Kc6 h4 3. Kb7 h3 4. Ka8 c3 5. bc3 Qb8 6. Rb8 h2 7. Rh8!

QChess.

Horwitz and Kling.

When I go on holidays I like visiting bookshops and having a look at the Chessbook section. Yes, today you can get anything anywhere, and more through the web, but … This September I found a book the second edition of which appeared in 1889 published in London by G. Bell and Sons. The title is CHESS STUDIES AND END-GAMES and contains the studies and endgames composed by Josef Kling (1811-1876) and Bernhard Horwitz (1808-1885) . The original first edition was published by the authors in 1851 and the 1889 edition was a revised and corrected one by Revd. William Wayte. The book has two parts, one of them devoted to “Chess Studies” and the other being a “Miscellany of Endgames”.

Many people think these type of books are useless: a lot of diagrams featuring composed positions to solve and nothing more. A quick glance at one or two of the positions , a possible (and most likely wrong) solution by seeing the apparent (and probably wrong) first move and a boring sneer. (It’s much better a book full of opening variations outdated since the very moment it goes to press, isn’t it???). Wrong approach.

I must confess there was a time I had that stupid attitude… Later, I realised how valuable solving studies,problems and endgame compositions to train one’s tactical skills is … I think it was Botvinnik who pointed out that there was no strategy in studies. As in most of the topics he wrote about he was right. You cannot solve a study or a problem by using strategical ideas or looking for deep strategical plans. These things have to do with pure calculation. Alexander Kotov , the man whose books taught how Chess is played to several generations of players, said that any work on this field was beneficial and useful to the player.

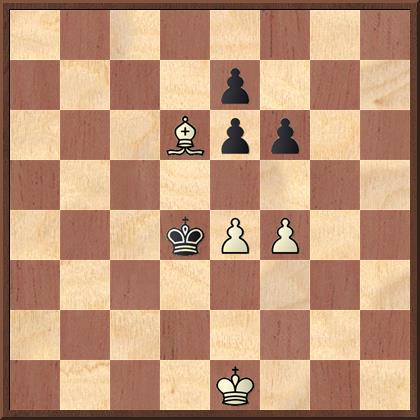

I have opened the book at random and found the following position:

Would you like to spend some time trying to solve it? White to move wins. This does not have a long solution. Apart from problems featuring mate in three, four moves I think it is not necessary (unless you were a genuine Chess study fan) to torture yourself trying to solve positions with solutions which may have nine, ten and even more moves (curiously enough, I have seen columnists which offer their readers combinative positions from actual games and the solution has seventeen, twenty and in some case over 25 moves (!!). These are, clearly, cases of sheer incompetence: you cannot pretend people to guess 20 moves in GMs’ games offering the position as a case of “combination”… )

But this book provoked a curious feeling on me: These two authors lived in the 19th century. Obviously they had their own lives, fears, pains, happiness, hobbies ,etc. though they devoted their lives to Chess. Over a century has passed and we know of them because of their work in Chess… What do we really know about those who preceded us in say, the last years of the 19th century and the first two or three decades of the 20th century?. All of them are now dead (I am speaking of those who lived in those years not of those who were born then). We read about their Chess lives, study their games and perhaps try to know what the places where they played were like in those years… But the man himself?. Of course the private lives of some of them are relatively well-known . Other ones’ are not so .

Solution to the study:

1. e5, Kd5 /2. Kf2, Ke4 /3. Kg3, Kf5/ 4. Kf3, Kg6/ 5. Bxe7 winning.

QChess.

Of Bishops and Knights.

Warning: Most of the contents in this post is or may be highly speculative. Many readers may have different opinions and your ideas may be as good or even better than the author’s. Unfortunately one reads many things passim and sometimes to find the exact words seems impossible. This is why have blended the assertions with the rethorical questions to imply that all what I want is to arise the doubt which may lead us to the truth, which in Chess is nearly always relative.

____________________________________________________________

One of the perennial topics in Chess is that of “what do you like best, the Bishops or the Knights?”. When we were young we all had a favourite piece…, and in many treatises by important authors we found something like: “well, it depends on the position: in open positions the Bishops and in closed positions the Knights. And the question is answered.

Wait a minute………..”Answered????”

That innocent question is full of venom. If you want to study the matter by yourself, here is some bibliography you should not miss (incidentally a proof that the question is far fom easy…):

SOLTIS: “Rethinking the Chess Pieces”

TIMMAN: ” Power Chess with Pieces”

WATSON: ” Secrets of Modern Chess Strategy”

Here you will find a wealth of modern ideas. Fortunately or not, those who have studied many f the books published during the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s of the past century have read the same things for years, and more if the authors were from the former Soviet Union. But in the meanwhile, and more during the last decade or so, new ideas were constantly appearing. Most of us read in a hundred of different books that “dictum” mentioned above: it was like a lethany which seemed to win points simply by repeating it: “the Bishops for open positions, the Knights for closed ones .the Bishops for…” ad infinitum. Then one day you take Watson’s book and all your deeply established foundations are suddenly blown out: that may be so in certain cases but not in all cases. On the contrary: the Knights prefer open positions while to take advantage of the Bishops it is necessary to close the position, stabilize it and try to open it later.

All leading top chessplayers devote much of their time to study all the nuances affecting this matter. This is a recurrent theme in the Soviet School Chess tuition system. For a non-Soviet today may be very difficult to understand the degree of effort they put for decades, dissecting openings, working on middlegame positions, determining why in everyone of those positions this Bishop should be exchanged for that Bishop or Knight or if in this or that particular case B + N was stronger than the Bishop pair, etc. Except in very specialised treatises you will not find these ideas when studying annotated games. Most GMs are reluctant to give away their secrets. Even when they are annotating their own games, they never disclose their opening preparation or say much about the way they find plans and ideas. Many annotators have no time, space or knowledge to explain clearly what is happening in the game they are analysing. Chess is a very difficult game, and trying to explain what a GM or a World Champion had in mind when he played this or that, integrating it in the frame of a whole game is not always feasible…

But remember: the leading GMs when training or studying, pay a lot of attention to the matter of Bishops and Knights. (You will have read another piece of advice like this one : “Pay attention to the pieces left on the board not to those absent”. As in mostother cases in Chess, another half-truth: in fact it is so, but before a piece is exchanged and abandons the board the GM knows why it should /must be exchanged and which of the opponent’s pieces should / must accompany it.) The corolary is: stop playing by inertia. The pieces on the chesschessboard conforms a delicate and very sensible structure: every move changes or may change the balance forever. Pawns cannot go backwards, so every Pawn movement alters the system. Space is controlled a different way by the different pieces. The advance of a Pawn + the exchange of a Bishop may condemn your position creating a permanent weaknesses on the squares of a certain colour (Nimzowitsch has this as one of his deadliest weapons). To reach an endgame with a static Pawn structure + the wrong minor piece may mean a sure defeat (in the same way that a Pawn-endgame may be lost for one of the sides while keeping a Rook or a piece may mean salvation, etc.)

It is very curious how the potentiality of the pieces can baffle even today’s chess programs. I have submitted some endgame compositions to Fritz 13. The positions were of the type: “White to move draws.” Some of these positions may how a heavy unbalance in the number and/or quality of the pieces involved and here lies their artistic value. Well, the program was unable to recognise the draw till it was made: in the process it was giving enormous evaluations to the Black side… I do not pretend this happens on a 100% basis, but if you find the adequate examples you will see a super- program going astray in an endgame problem.

I had always wondered what the Soviets trainers taught their pupils (the likes of Spassky, Karpov, Kasparov, and so on). The more I tried to find an answer, the more opaque the situation became. Well, in the end, gathering information from here and there , and apart from many other aspects, I came to the conclussion that one of the lessons was that of Bishops/Knights. Apparently ,Karpov’s trainer, S. Fuman, instilled into his pupil the love for the Bishops (incidentally, Furman also trained Korchnoi, another devotee of the Bishops…). If you have a look at Karpov’s games, two details appear immediately: he mastered the difficult art of Rook endgames, and there is a very high nmbers of endgames in which the Bishop is involved.

In my opinion, I think some of the lessons the Soviet Chess teachers loved to teach was those of the use of the Bishops, the strength of the Bishop pair, the handling of Bishop pair vs. N+N and B vs. N with and without Rooks …

So from now on, when you study the games of the great, pay attention to the use they make of the minor pieces, try to understand why there is an endgame with this or that correlation of forces, why they tried to exchange Bishops, or BxN or why they tried to keep Bishops or Knights on the board.

As Soltis would say: “the essence of Chess”.

1.- Powerful Knights:

W.:V. Korchnoi (0)

B.: V. Tukmakov (1)

Reggio Emilia 1988

1. Nf3 d5 2. c4 c6 3. e3 Nf6 4. Nc3 e6 5. d4 Nbd7 6. Qc2 Bd6 7. Be2 0-0 8. 0-0 dc4 9. Bc4: b5 10. Bb3 Bb7 11. e4 c5! 12. Nb5: Be4: 13. Qe2 Bf3:! 14. gf3 (14.Qf3: Bh2: 15.Kh2: Qb8) 14… Bb8 15. f4 a6 16. Qf3 Bf4: 17. Bf4: ab5 18. Bd6 cd4! 19. Bf8: Qf8: 20. Rac1 Rd8 21. Rc7 Nc5 22. Rfc1 Nfe4 23. Re1 Nd2 24. Qc6 Nd3! 25. Rd1 Ne5 26. Qc5 Ndf3 27. Kg2 d3! 28. h3 g5 29. Qf8: Kf8: 30. Rb7 Nd4 31. Rc1 Nb3: 32. ab3 d2 / and White resigned.

2.- Parallel Bishops:

W.: L. Ljubojevic (0)

B.: J. Pinter (1)

Belgrade 1984

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nf6 3. Bb5 a6 4. Ba4 Nf6 5. 0-0 Be7 6.Re1 b5 7. Bb3 d6 8. c3 0-0 9. h3 Na5 10. Bc2 c5 11. d4 Qc7 12. Nbd2 cd4 13. cd4 Bb7 14. d5 Rac8 15. Bb1 Nh5 16. Nf1 Nf4 17. Ng3 Bd8 18. Bf4: ef4 19. Nh5 Nc4 20. Re2 Ne5 21. Rc2 Qa5 22. Kf1 Nf3: 23. Qf3: g6 24. Rc8: Bc8: 25. Nf4: Qd2 26. Nd3 f5! 27. ef5 Bf5: 28. Qe2 Qg5 29. g4 Bd7 30. Bc2 h5 31. Bd1 Kg7 32. Qe4 Bb6 33. Be2 Re8 34. Qf3 ?! (Qg2!?) 34… hg4 35. hg4 b4! 36. a4 ba3 37. Ra3: Rf8 38. Qg3 Bb5 39. Qd6: Bd3: 40. Rd3: Rf2: 41. Ke1 Qc1 42. Bd1 Qb2: 43.Bc2 Qa1 / White resigned.

Two beautiful games with a lot of variations to be analysed.

Questchess.